Insights into the controversy swirling around Jeanine Cummins' novel

Plot and Publicity

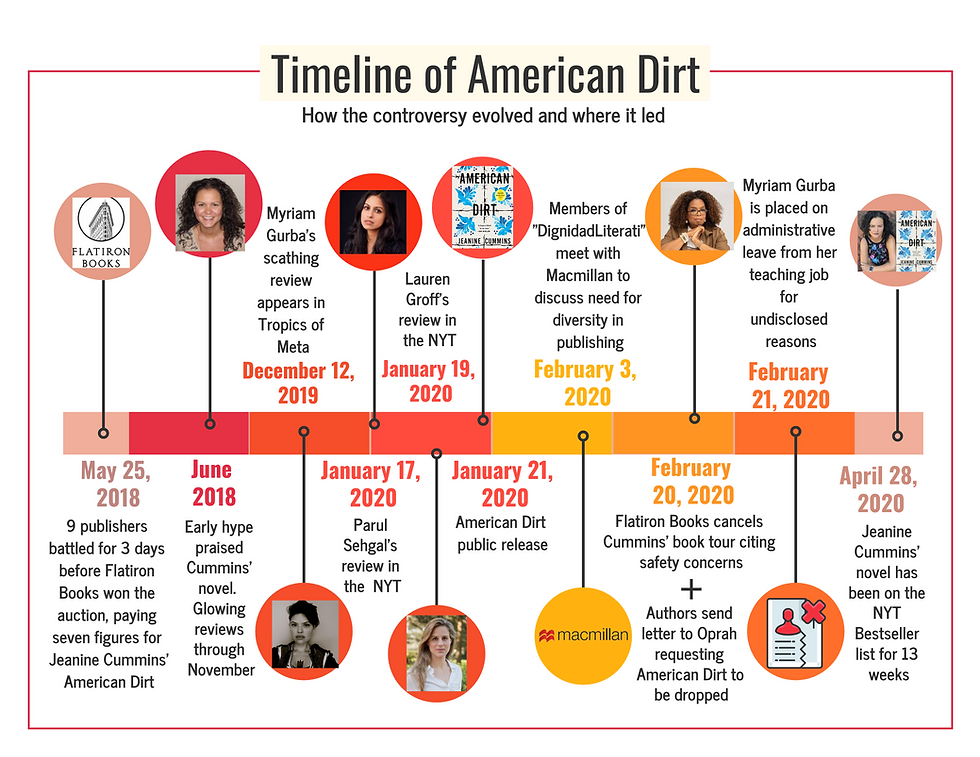

If you live under a literary rock, you may not know about the furor that has erupted over Jeanine Cummins’ novel, American Dirt, released from Flatiron Books on January 21st of 2020.

The novel is the story of Lydia Perez, an educated bookstore owner living in the Mexican town of Acapulco, Mexico, with her journalist husband, Sebastian, and her 8-year-old son, Luca. While attending her niece’s Quinceanera party, thugs move in and shoot everyone in Lydia’s family, her husband, her mother, her sister, her niece…sixteen people in total. At the moment of the shooting, Lydia just happens to be in the restroom with her son, Luca, allowing them to escape the carnage.

The police believe the shooting was retribution for a profile piece on the leader of a powerful drug cartel, a man known as La Lechuaza, “the Owl.” It turns out that this same man is Javier, Lydia’s close, almost-intimate-but-not-quite-friend from the bookstore, an attractive older man who shares the same tastes in books as Lydia does. She did not know what he did for a living until her husband’s profile piece informed her of Javier’s real occupation.

After the massacre, Lydia plans her escape with Luca after being threatened with death by Javier. The rest of the book chronicles their harrowing journey as migrants headed to the United States, the characters they meet, and the brutal hardships they endure.

American Dirt’s pre-publication hype was huge. Don Winslow, an American crime writer, called it the next Grapes of Wrath. Kirkus called it, “Intensely suspenseful and deeply humane.” Jeanine Cummins’ book was enthusiastically endorsed by Stephen King, Ann Patchett, Sandra Cisneros, and was chosen the selection for Oprah Winfrey’s book club, a guarantee of being a best-seller.

So what, you may be thinking, caused the uproar that’s rattled the publishing world?

Myriam Gurba’s review got the ball rolling.

The positive tide turned negative

Myriam Gurba is an author, feminist, and performance artist with a Mexican heritage. She’s written two books, Painting Their Portraits in Winter: Stories and Dahlia Season: Stories and a Novella. Both works examine Mexican heritage through a “feminist lens.” She was contracted by MS. Magazine to write a review on American Dirt, but Gurba says that she was angry from the time she received a review copy of the book with a letter from the publisher and saw Cummins’ comment that she wanted to humanize the “faceless brown mass. . . That she wanted to give these people a face.”

“The phrase “these people” pissed me off so bad my blood became carbonated.”

You need to read Gurba’s review to make your own decisions about the resulting controversy and the aftermath for all concerned. Be forewarned: Gurba’s words hurt ME to read and I had nothing to do with the authoring or publishing of American Dirt. It was painful, not because of what she said, but because of how vehemently she said it. The word “vituperative” comes to mind, but that doesn’t mean that her points weren’t valid.

Gurba’s review, originally contracted for Ms. magazine, never ran. Gurba received a “kill-fee,” a portion of the original contracted amount, and was told that she did not have the literary clout to publish something so negative. But the piece was written, she felt strongly about it, and she published it in “Tropics of Meta,” an academic blog with the goal of providing new perspectives in current and cultural events.

Gurba’s basic premise has three prongs:

American Dirt was only published and promoted zealously because Jeanine Cummins is white. Latino writers usually can’t sell their works to major publishers, and when they do, they are not afforded the kind of hype that Cummins’ American Dirt was given.

Cummins’ work is NOT original and draws on the works by people of color who have actually experienced what she’s writing about and who haven’t received any acclaim for their writing.

The novel is a white-washing of real issues to pander to a white, American audience for the sake of sales.

In her essay, “Pendeja, You Ain’t Steinbeck: My Bronca with Fake-Ass Social Justice Literature,” Gurba loudly criticized American Dirt for stereotyping the Mexican people, the experiences, and for making everything in Mexico look bad. She said,

“the nicest thing I can say about Dirt is that its pages ought to be upcycled as toilet paper, the editors hauled out the guillotine.”

Gurba’s response started a pandemic of responses. (Sorry, the word “pandemic” seemed appropriate.) Latino writers began to echo Gurba’s sentiments and rebel against the book and the publishing industry, criticizing companies eager to take on work by people not of the culture and who have never experienced what they are writing about. Celebrities who had posted positive Tweets about American Dirt withdrew them. Reviewers stopped commenting on the novel. Terms like “trauma porn” were applied to the book.

One perspective may have claimed that it was only a small segment of the population, usually those of Latin origin, who declaimed the novel. Then came two less-than-positive reviews in the New York Times. Both critics acknowledged the truth in Gurba’s criticisms.

Parul Sehgal’s review in the New York Times, “A Mother and Son, Fleeing for Their Lives Over Treacherous Terrain” points out the tortured language and far-reaching similes before acknowledging that the book feels like an outsider looking in, not an authentic experience, and seems to see being “brown” as a kind of “otherness.”

Still, the book feels conspicuously like the work of an outsider. The writer has a strange, excited fascination in commenting on gradients of brown skin: Characters are “berry-brown” or “tan as childhood” (no, I don’t know what that means either).

Two days later, also in the New York Times, another review by Lauren Groff says this:

In contemporary literary circles, there is a serious and legitimate sensitivity to people writing about heritages that are not their own because, at its worst, this practice perpetuates the evils of colonization, stealing the stories of oppressed people for the profit of the dominant. I was further sunk into anxiety when I discovered that, although Cummins does have a personal stake in stories of migration, she herself is neither Mexican nor a migrant.

The outcry against the book was so loud that 142 authors wrote and signed a joint letter to Oprah Winfrey asking her to withdraw American Dirt as her choice of Book Club choice.

Oprah declined and instead decided to host a special event on Apple TV that brought in three Latino authors to discuss the differing perspectives on American Dirt with Jeanine Cummins.

Do you have to be of the culture to write about the culture?

Years ago, I was chosen to go on a Fulbright Study Abroad trip to China. For more than six intense weeks, a fellow instructor and I studied in the presence of Chinese scholars and translators. We toured the country. We experienced cooking, classrooms, museums, art, culture, historic sites. We fell in love with the people and the country. When we returned, my colleague and I asked to teach an Introductory course on Chinese culture at our community college.

Two respected, popular instructors. No one could have been more enthusiastic, more excited about introducing our students to a country they might not know anything about, to broaden their perspectives and encourage tolerance of a different culture.

The course was designed and put on the schedule when a Chinese instructor protested, declaring that we couldn’t possibly teach an introductory course because we were not Chinese. Our course was canceled.

So at first, I thought I knew what all the controversy was about, the old “if-you’re-not-of-the-culture-you-can’t-write-about it” argument.

But that’s not the issue with the American Dirt controversy.

It’s not that you can’t write about something outside of your experience. It’s that if you choose to do so, you have to do it exceptionally well. You have to know the places, the people, the geography, the topography, the legends, and the differing viewpoints of the native peoples that the writing doesn’t sound like is not as someone looking in, but as someone who has integrated every part of that culture into the narrative.

Critics weren’t saying that Cummins couldn’t write about something she has never experienced or about a culture different than her own. People do it all the time. Males write female characters. Women write male characters. Authors across the globe have ventured into unfamiliar territories and written compelling books about different peoples.

Oprah steadfastly backs the right of ANY writer to write about any CULTURE:

“I fundamentally, fundamentally believe in the right of anyone to use their imagination and their skills to tell stories and to empathize with another story.”

The controversy comes NOT because a non-native wrote American Dirt, but because so many people feel that the book is done poorly, filled with stereotyped characters, inaccuracies in descriptions, and an attitude of white, American, superiority.

The controversy was fueled by five additional factors and differing perspectives:

Cummins wrote that she wished someone “browner” had written American Dirt, but since they hadn’t, she would, saying. “If you’re the person who has the capacity to be a bridge, why not be a bridge?” The opposite perspective argues that so many “browner” HAVE written about their experiences — authentic ones — but haven’t received the hype.

Cummins’ posted a photo on Instagram of a fan’s manicure which depicts the cover of her book, barbed wire around blue and white Mexican tiles. Critics perceived that as a callous disregard for the pain of the border crossing and a symbol of oppression. (As a writer, I think she was probably just bowled over by the loyalty of such a fan, or in wonder of a person who does such detailed nail art of current book covers. And this fan was helping spread the word about Cummins’ new book.)

At a dinner celebrating the release of American Dirt hosted by Flatiron Books, the centerpieces were the books wrapped with barbed wire. Again, critics saw the decorations as a flagrant flaunting of pain, but it’s possible that a marketing and events person saw the centerpieces as a clever tie-in to the book cover and topic, not as a callous gesture of disregard.

Four years ago, Cummins identified as white. Now, she says she’s Latino, based on her Puerto Rican grandmother. Cummins says that she struggles with finding her true identity.

Cummins and Flatiron Books referred to her husband as an undocumented immigrant, without relaying the fact that he was Irish and his experience had nothing to do with what migrants from Mexico face. The flipside? Yes, her husband is an immigrant…from Ireland.

Controversy creates revolution

Gurba’s vitriolic review served as the basis for a revolution of sorts. Latino authors joined her cry and protested the publishing industry, starting a movement called #DignidadLiteraria. The purpose of DignidadLiteraria, according to Cummins, was to work toward

“racial dignity within the publishing industry by pushing for systemic change through grassroots organizing. Young people of color, including my students, were also inspired to translate their anger into direct political action as well as the written.”

According to the online publication, Vox, one organization for young people is responding. Immigrant Youth Group United We Dream is petitioning Oprah to include more Latinx and immigrant authors in the Book Club selections.

The uproar over American Dirt did produce a meeting between the Latino authors of Dignidad Literaria and Macmillan Publishing to discuss the need for diversity in the publishing industry and strategies for increasing inclusion of minority groups.

Death threats. Really.

To help you understand the “heat” of this debate, authors who signed the letter to Oprah received death threats. According to Flatiron Books, Cummins’ book tour was canceled because of other threats to some booksellers and the safety of the author.

Authors who received threats because they commented publicly against American Dirt are putting their threats into a “Death Quilt,” commemorating the cost of standing up to the established majority. Author Roxanne Gay asserts,

“People need to realise what real censorship looks like. They need to understand how unsafe it can be to challenge authority and the status quo.”

Aftermath

In a different essay in Vox, Gurba discusses the aftermath of her criticism. Gurba teaches “The psychology of anger” in her classes and encourages students to rage instead of despair. Gurba’s students used her angry essay against American Dirt to voice complaints about a teacher who they viewed as racist. Gurba added her voice to that. She was put on administrative leave and escorted out of the school building, later informed that she was on leave because she had “intentionally disrupted the educational environment.”

Gurba believes differently:

“Given the timing, as well as the lack of reasoning beyond “disruption,” I believe my critique of American Dirt, and my critique of the school district’s poor job of handling the students’ accusations, is the reason the district placed me on administrative leave.”

As I’ve learned again and again, if you speak out against racism, there are risks you must take on.

As a writer, I’m sympathetic to Jeanine Cummins whose book was so fully touted prior to its release, only to have so much negativity pile on. Her intentions were to create empathy for a population she felt wasn’t fully understood. I feel bad that her book tour was canceled and that she was blindsided by the furor and vitriol her book inspired. I learned that the book-writing business is fraught with perils hiding in perspectives you might not see when you’re writing. I’m sorry for her pain simply because I’m a writer who can sympathize, but it’s hard to feel TOO sorry for her since she got a seven-figure advance.

The controversy hasn’t hurt sales, either. Currently, American Dirt is 3rd on the New York Time’s Fiction Hardcover list and 4th on the Combined Print and E-Book List.

If you love books, you'll want to read more about both classic and contemporary "reads" in Book Talk.

Comments